The COVID-19 pandemic effect has been faced by every individual, in one way or another. The world's COVID-19 response concerning people living in informal settlements, migrants, refugees, and other ultra-vulnerable populations has been slow and inadequate. It emphasizes serious concerns about health inequality, as well as people lacking human rights and dignity including access to basic services and infrastructure to survive the pandemic. India has been one of the worst affected countries since last year. The virus has intensified the already existing social and economic inequalities and has highlighted the growing gap between the rich and the poor. In April 2020, as Mumbai emerged as the epicenter of the pandemic in India, extensive imbalances in the country’s financial capital were exposed, with the poorest being worst impacted by the lockdown and in dire need of relief.

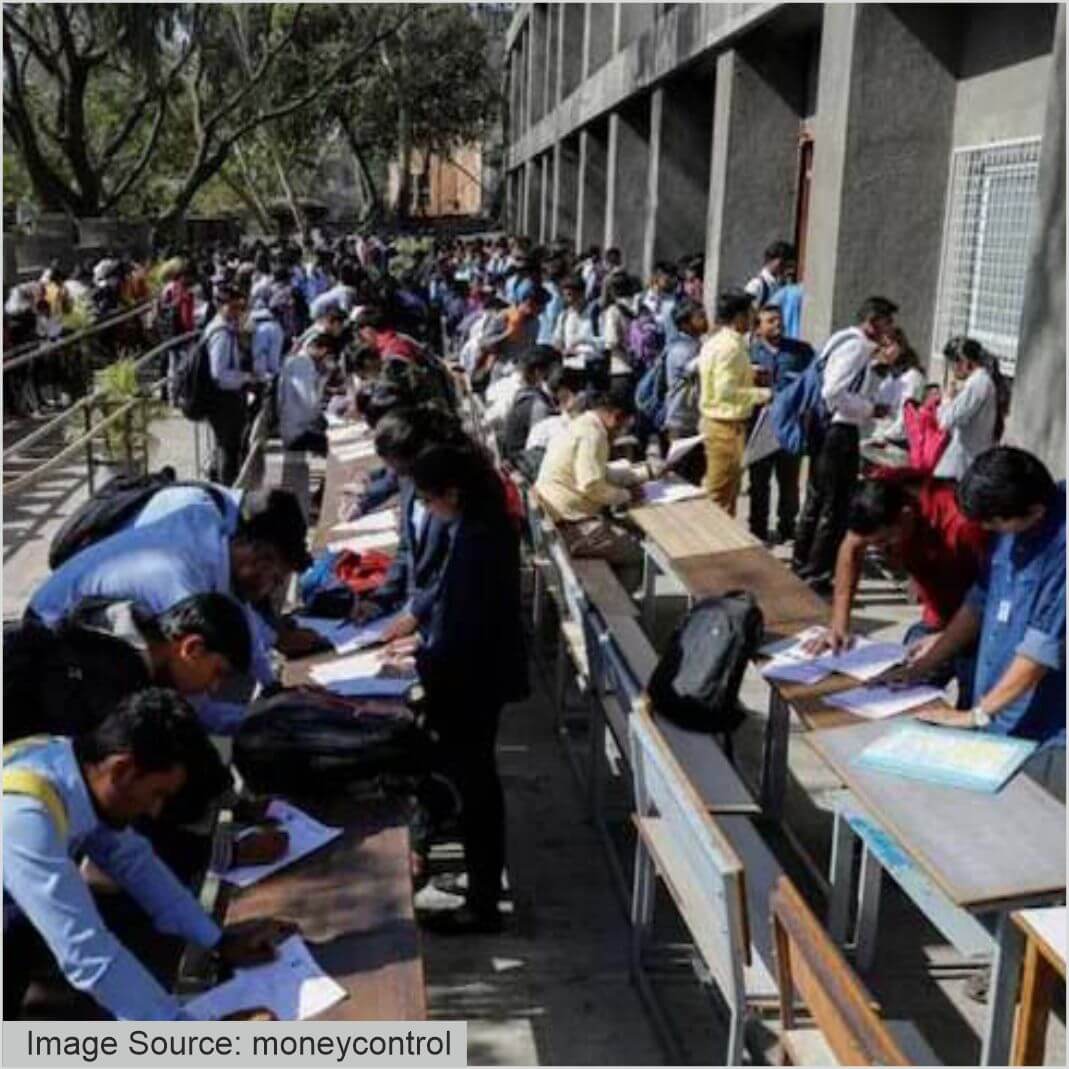

India is a country where over 80% of the population works in the informal sector, the lockdown amounts to a substantial shutdown of economic activity. Informal workers, the majority of whom can be categorized as the “urban poor” form 69.1% of urban India’s workforce and remain largely invisible—both as workers and as residents. As of May 2020, the four megacities in India; Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata, comprised 40% of the total cases in the country.

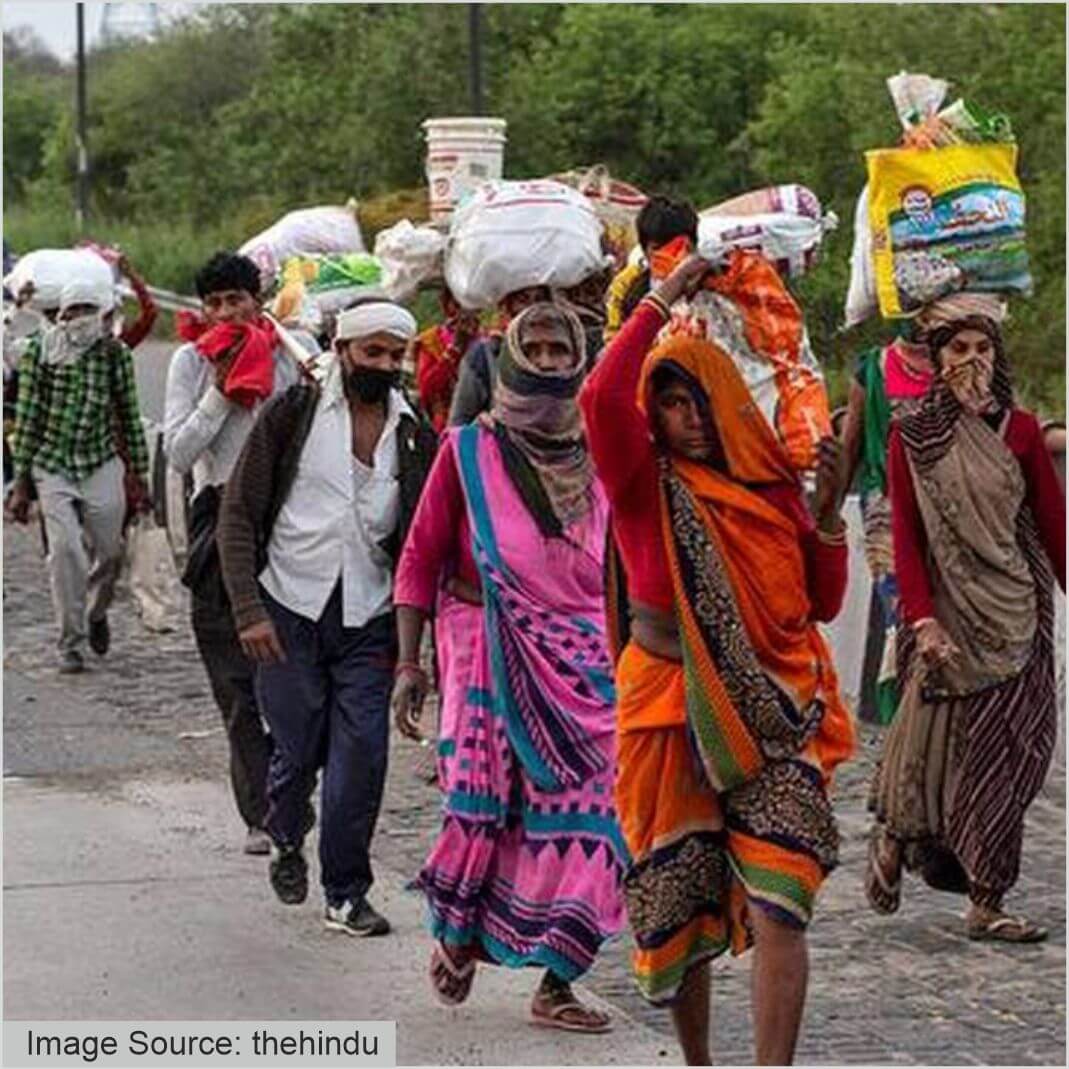

When the lockdown was announced, lakhs of these workers and their families traveled back to their villages by any means. This section of the population is the one without any social security. Many studies have shown that the urban poor have suffered more in the pandemic as compared to their rural counterparts, who were supported by the benefits of the Public Distribution System (PDS).

A study undertaken across two major slums in the cities of Lucknow and Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh found that the lockdown severely impacted economic activities. 79% of urban poor households reported that at least one family member had lost their income source due to the economic shutdown, and additionally, 56% experienced a decline in their incomes when compared to before the crisis.

UNEMPLOYMENT:

When the pandemic hit, the Indian economy was already in the most prolonged slowdown in recent decades. On top of this, grave problems such as a slow rate of job creation and lack of political commitment to improving working conditions trapped a large section of the workforce without access to any employment security or social protection. Youth were unable to find job opportunities, and those who were already employed were losing their means of livelihood. Unemployment has been on the rise.

An analysis done by a team of the Azim Premji University shows that the pandemic has further increased informality and led to a severe decline in earnings for the majority of workers resulting in a sudden increase in poverty. Women and younger workers have been disproportionately concerned. Households have coped by reducing food intake, borrowing, and selling assets. The borrowing of food among the urban poor has led to a decrease in the nutritional quantity and quality of the foods they consume.

POVERTY:

The pandemic and its implications are said to have increased the poverty levels in India. India’s middle class may have shrunk by a third due to 2020’s pandemic-driven recession, while the number of poor people — earning less than ?150 per day — more than doubled, according to an analysis by the Pew Research Center. The lockdown triggered by the pandemic resulted in shut businesses, lost jobs, and falling incomes, plunging the Indian economy into a deep recession.

India’s middle class may not be as wealthy as its peers in the United States and elsewhere, but it makes up an increasingly potent economic force. Household incomes and overall consumption have weakened, even though the sales of some goods have increased recently because of pent-up demand. Many of the hardest-hit people come from India’s merchant class, the shopkeepers, stall operators, or other small entrepreneurs who often live off the books of a major company.

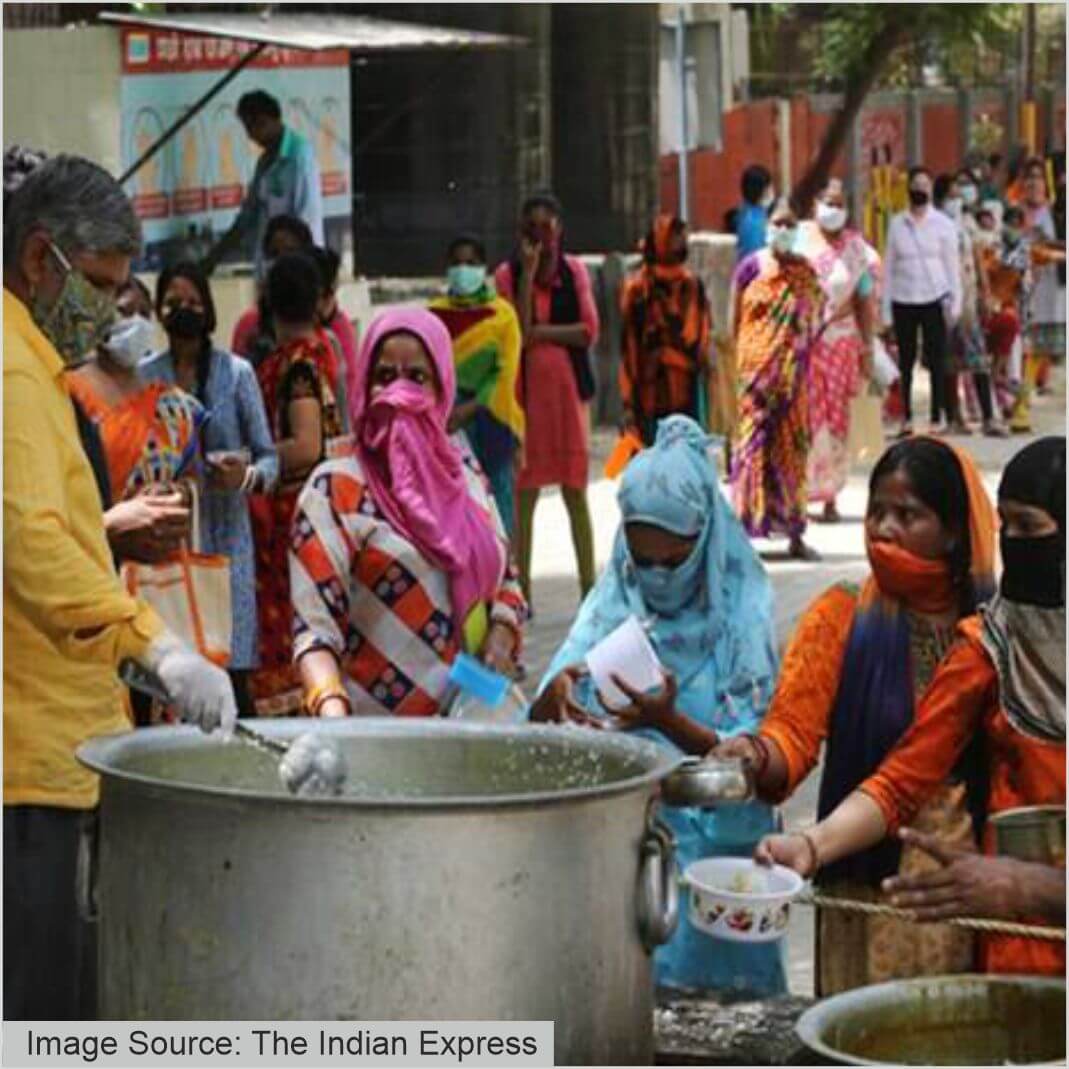

HUNGER:

Overall, levels of hunger and food insecurity are high in the pandemic, with very little hope of the situation improving without measures specifically aimed at providing employment opportunities as well as food support. Roughly two-thirds of nearly 4,000 persons interviewed by Hunger Watch reported that the quantity of food they consumed in October 2020 had either “decreased somewhat” or “decreased a lot” compared to before the lockdown.

GOVERNMENT POLICIES:

Identity documents, such as ration cards, voter identity cards, bank accounts, Aadhaar cards, worker’s registration cards, etc, are essential requirements to access welfare schemes and entitlements linked to food, livelihoods, and healthcare. Additionally, owning these documents gives the urban poor a legal identity within the city’s system, citizenship, and rights. It doubles up as a form of proof to be able to access basic services such as water, sanitation, electricity, and housing.

The lack of identity documents has meant the failure to access government relief. During the lockdown, this was especially severe given that the ability to earn was hindered and households were dependent on relief.

WHAT DOES CHF DO?:

Child Help Foundation aims to accomplish the goals set by the United Nations (UN) to end Hunger by the year 2030. The Zero Hunger Sustainable Development Goal (SDG-2) set by the UN plans to “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture". To make this possible, CHF in partnership with Khushiyaan Foundation has started the Roti Ghar initiative, under which, we provide warm, nutritious meals to 1800 underprivileged children daily.

Through our Roti Ghar program, people are working tirelessly to feed children from poor and disadvantaged backgrounds. along with providing them with the nutrition they need. Roti Ghar is now feeding underprivileged kids every day in different locations across India including Thane, Mumbai, Delhi, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru.

In the year 2021, India has been hit by the second wave of the COVID-19 virus, creating high amounts of pressure on the healthcare system of the country. Around 2 lakh cases are being registered every day; the number was way lesser in the year 2020. Child Help Foundation started the ‘Breathe India’ campaign to try and reduce the burdens off the hospitals treating COVID-19 patients, by facilitating oxygen concentrators. We have been successful in providing oxygen concentrators to several hospitals throughout Maharashtra to date.

Child Help Foundation works at the grassroots level to uplift the lives of the underprivileged citizens of India. To support the needy, throughout the pandemic period, CHF’s mission has been to make essential resources available to them. CHF distributes Ration Kits to needy families and individuals with essential materials like food grains, salt, sugar, basic spices, cooking oil, and soaps. This distribution usually takes place on a community level, aiding many families all at once. We plan to reach and support as many people as possible, to take care of the needy.

These times are tough for us all. CHF believes that we can come together and fight these battles against COVID-19 as one! Let us all come together and save our fellow countrymen who are in dire need of help. We need your constant support to make sure that help is being reached to the poorest of the poor.

Click on the link to connect with us: Covid-Relief